5. Sport and achievement

Relationship between sport and achievement can be examined form two aspects: on the one hand what factors affect whether somebody do sport or not (social aspects of this question is examined in the next chapter), and who are the successful athletes, on another hand, what is the effect of sport activity on the academic and non-academic achievement (Eitle, Eitle 2002). In this chapter the second approach is applied. Studies on student achievement have been extensive: the topic is relevant from the perspectives of education policy, the economics of education and the entire country (serving as a tool of measuring economic productivity) and the sociology of education as well measuring social mobility. Most studies consider student achievement as scores of standardised tests measuring some sort of skills, abilities and knowledge, while researchers emphasizing the complex nature of achievement denote such interpretations too narrow and thus apply soft, subjective indicators of student achievement (for example persistence and engagement in studies, willingness to study further, extra study work, moral judgement ability, working during studies etc).

5. 1. The impact of sports on academic achievement

Research results on the correlation of sports and student achievement are not consistent (especially in the case of upper-secondary school and higher education students): some found positive (Hartman, 2008; Field et al., 2001; Castelli et al., 2007), others found negative (Purdy et al., 1982; Maloney & McCormick, 1993) influence of sports, while a third set of research results have not identified any correlation of the two (Fisher et al., 1996; Melnick et al., 1992).

The positive effect of sports, regular physical activities as well as civil activity have been associated with personality development (Fényes & Markos, 2019). According to the personality development theory, sports develop personality by teaching to respect hard work, perseverance, improving a number of skills, self-confidence, maturity, social competences, increasing school participation, students’ educational and other performance, thus contributing to students’ school achievement (Brohm, 2002; Miller et al., 2007; Rajesh, n.d.). This is especially true if students would like to participate at college sports (Eitle, Eitle 2002). Besides, sports strenghtened social relations among students, teachers, parents and schools, thus increased athletes’ social capital, which also had a positive impact on their achievement. However, we should also note that the different sports and sporting forms have diverse influence on the various dimensions of academic achievement (Brohm, 2002). Consequently, it is important to define sporting habits as a multi-dimensional concept and apply this complex concept for analysing the different dimensions of achievement (Castelli et al., 2007).

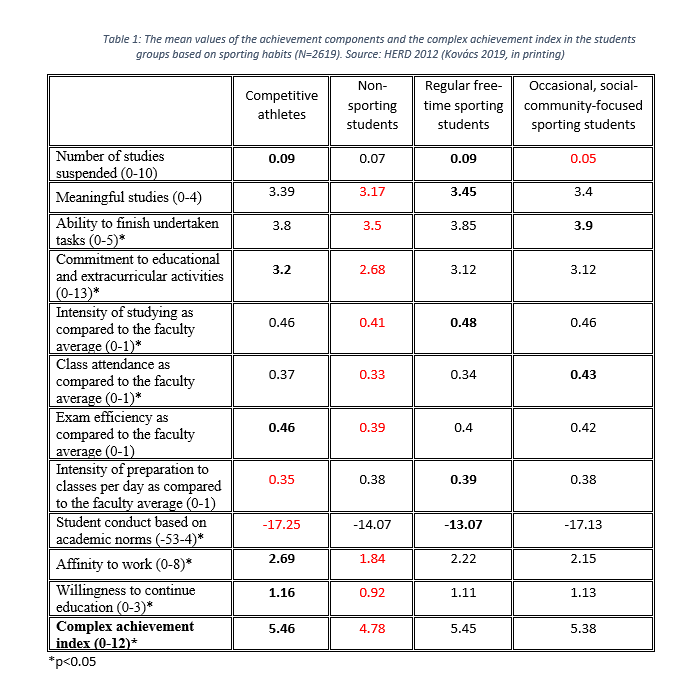

The results of our previous research programmes among students of Debrecen showed that competitive- and regular free-time sports had extemely positive effects. Except for two dimensions, the students doing sports were found to be performing outstandingly well. All in all, athletes pursuing competitive sports were the best, demonstrating that they were capable of studying effectively while they regularly participated in sports events. They are future-oriented, persistent, possess good organizational skills, work hard and are able to perform equally well in sports and in their studies. Those who pursue sports as a free-time activity, usually tend to dutifully meet their academic obligations, they see the goal of their studies, and intensively prepare for their lessons and exams (table 1). The positive effects were the same even when social background variables were included in the research (Kovács, 2015).

Those research results that did not find significant correlation between sporting and academic achievement (Eitle & Eitle, 2002; Fisher et al., 1996; Melnick et al., 1992) support Coleman’s social capital theory (1961). According to Coleman, extracurricular activities, such as sports, contribute to the acceptance of sporting youths, the establishment of their roles and authority among their peers and as a result of the popularity of sports, they build stronger relations with their teachers and parents. Consequently, their social capital increases, which impacts their educational achievement positively. This culminates in a so-called zero-sum situation as sporting consumes energy from learning, what is more, schools emphasize their athletes’ achievements and partly consider those as their success, thus by highlighting sports and sport achievements they also contribute to the worsening of academic achievement (Eitle & Eitle, 2002; Miller et al., 2007). As a result, they lose the benefit of social prestige, recognition and capital or the scale might move to the negative dimension and athletes perform worse at schools. This is also supported by Hauser and Lueptow’s research (1978). According to them, sporting secondary school students had better academic achievement by the end of secondary schooling but their development was smaller (measured in points) than their non-sporting fellows, thus their performance relatively decreased.

Coleman’s social capital theory is utilised in a different way in the world of college sports. While sporting secondary school students have high prestige among peers and teachers due to their sport achievements, and their popularity helps them to build social relations both inside and outside of schools, their relations are limited to their sports communities in higher education, which delimits them from other communities, thus sporting decreases students’ social capital. A well-known expression for this situation is “dumb jock” (Bowen & Levin, 2003).

Further causes for the negative or neutral impact of sports are constituted by the influential power of social background variables on achievement factors. Due to social background, a sort-of self-selection process occurs in high school and college sports, which raises the question whether socially better-off students start to sport and are these students the same as those who perform better on standardized tests due to their better social status and thus get selected for higher education studies and obtain degrees. Research results confirmed that talented but disadvantaged athletes (for example, Afro-Americans) that study at universities/colleges with sport scholarships might perform worse academically due to their disadvantaged situation (in many cases this begins at secondary schools) (Eitle & Eitle, 2002; Eitzen & Purdy, 1986; Melnick et al., 1992; Maloney & McCormick, 1993; Sellers, 1992; Upthegrove, 1999). Purdy et. al (1982) found the same: they had researched more than 2000 college/university athletes for 10 years and found that athletes were less prepared and performed worse academically than their non-sporting peers. Not all athletes performed at the same level: students with football and basketball scholarships, Afro-Americans and participants in paid sports performed the worst. Besides, the phenomenon is more complicated as a longitudinal research project examining university/college athletes in the entire USA for decades found that among lead athlete university students, the ratio of disadvantaged students is not higher, what is more, they are more likely to have beneficial social status and still, they perform worse than their non-sporting peers and are more likely to belong to the student groups with the worst achievement (Shulman & Bowen, 2001).

In the continuation of Shulman, Bowen’s research (2001) Bowen and Levin (2003) researched athletes, coaches, sports and university leaders from the different sports organizations of 32 higher education institutions with quantitative and qualitative methods. They differentiated recruited athletes that are selected by coaches from competitive athletes that belong to lower-level leagues and participate at competitions from free will (walk-ons) and compared them based on various criteria (for example, achievement indicators) to non-sporting peers and female athletes. Their results show that non-sporting students had the best achievements while elite male athletes, members of the highest level university sport leagues and the most popular American sports (American football, ice hockey, basketball, gymnastics) performed the worst academically. Among the latter, the ratio of those that belonged to the worst performing one-third within their own groups was the highest. This is partly explained by the fact that these athletes performed worse at secondary schools already but coaches select them to recruited athlete teams for their extraordinary sport achievements, which worsen their achievement in higher education due to their sports obligations. Another explanation is that recruited athletes are more likely to come from disadvantaged background but this was not confirmed, recruited and competitive athletes are characterized by similar social background but received social aid and compensations for social disadvantages from universities to a larger extent than their non-sporting peers. This also verifies inequalities in social background but we have to note that such a measurement and interpretation of social status is extremely narrow.

The blind Side (video) is an Oscar winner movie (role player: Sandra Bullock) about a disadvantaged talented football player, who was adopted by a rich family. The movie introduces the role of family, the inequalities of entry into elite sports and stereotypes, the interrelation between elite sport and academic achievement, and how can sport and education contribute to protrusion from the disadvantage

Control questions

What are the approaches of relationship between sport and achievement?

What are the positive effect of sport on academic achievement?

What theories and research results do show the negative or neutral impact of sport on academic achievement?